The word benefits, for most people, is usually defined by their personal association to the word, for example through Social Security benefits or medical benefits. By merely inserting the word benefits in any sentence, it immediately seems to imply something good and positive.

When the word co-benefits is used, it is usually invoked in the context of providing synergistic benefits, an important concept in sustainability and resiliency in responding to a climate-change challenged world. A common example of co-benefits can be seen in green roofs’ ability to provide stormwater management, reduce the heat-island effect, increase a roof’s life, reduce energy use in the building, and offer a potential green space to enjoy.

These are all positives and should be part of a healthy, regenerative environment. But what if some or all these benefits are not shared equally or equitably, or access is limited? Are the benefits still as beneficial and for whom?

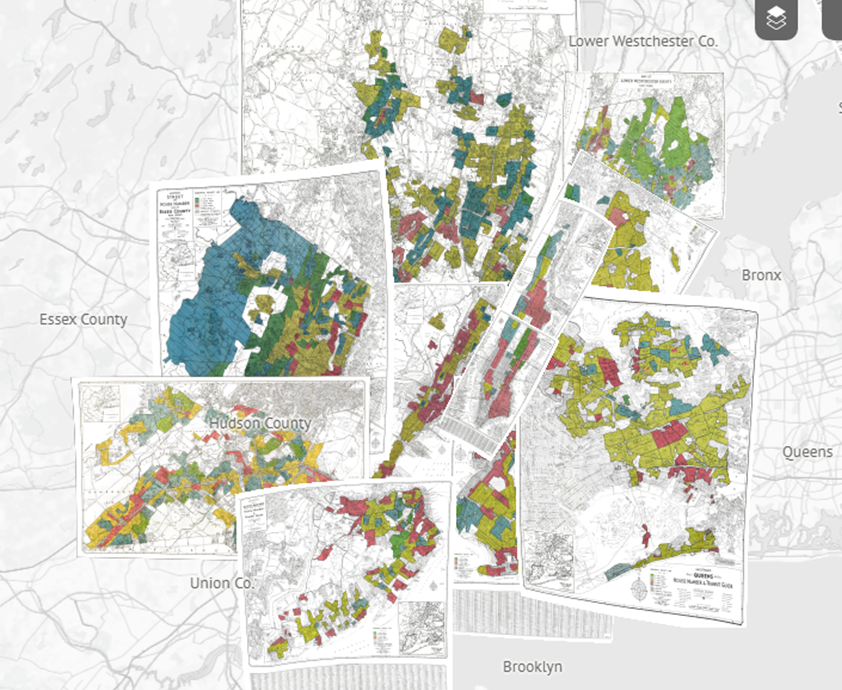

Recent research on tree canopies has shown that there was a calculated unequal investment in where trees were planted within American cities, following the patterns of redlining, disinvestment, and racial segregation over the past century.

The research shows that not only did lower-income areas have less tree canopy but the trees that were planted were smaller than those planted in wealthier neighborhoods. One could say that a benefit of increasing the tree canopy was provided to all the residents of a given city. However, the benefit was unequally and unfairly provided.

Take another example of a report released in February 2021 by the City of Orlando in the Orlando Energy Burden Report as part of the American Cities Climate Challenge. Even though citywide there is a decrease in energy burden, conditions are worsening in some of the highest burdened neighborhoods. According to the report, ”while the average burden has been improving across the city, some of the most burdened areas are not sharing in these benefits.”

The report summary explains that spending a high percentage of household income on energy costs is connected squarely to equity issues like healthcare and race, an historic continuation of systemic bundling and discarding groups of people based on race, class, and income.

Affordable housing

By selecting sites with less than ideal conditions, developers can drive down their land-acquisition costs while maximizing their return on investment, and in turn, are then rewarded by collecting valuable tax credits. The result is a repetition of the cycle of placing frontline communities back on the front line, in unhealthy environments for low-income communities.

Consider my family’s quest to obtain an apartment through the affordable housing lottery in New York City. Too many times, when we visit the project, it is in a marginalized area in proximity to major transportation arteries, in flood zones or near heavy industrial areas. Within the project itself, affordable units are selected based on market rentability, designating the least desirable units as affordable. This usually equates to compromised views, coughing proximity to subways and highways, and smaller floor plans; closets seem to be considered a luxury.

One could argue that the building is new, providing up-to-date appliances with perhaps some shared amenities. But there is a missing requirement in exchange for developer tax credits awarded for including affordable housing units in the project: a criterion that needs to be met for quality of life. Too often, the very conditions that the tenant is trying to move away from comes back full circle. The tenant is looking for a healthier, safe environment in which to live. It could be argued that being offered a bright and shiny brand-new building with new appliances is all that is required and isn’t that enough?

Is it enough? No, it is not. The message we hear is that because of our lower income, we only deserve the smaller-size units with maybe closets in the bedrooms, access to a laundry room not an in-unit washer and dryer, with affordable units that were pre-selected during the design process to be located in the least desirable locations within the building.

This is a market-driven approach that reinforces the entitlement of those with greater means and marginalizes those who occupy the affordable units. It is a positive feedback loop in the most negative way possible. The benefit ultimately only benefits the developer, not the prospective tenant; it is stolen wealth over the generations perpetuated by the complicity of government and developers.

Should the developer be held to a higher standard of delivery for housing services? Damn straight. Equal access to benefits, the equitable distribution of these benefits and ultimately, the elimination of institutionalized discrimination are all directly linked. Based on the level of need, tenants of low-income housing should be entitled to proportionally more benefits and amenities.

So how can this be realized? So far, we have looked at some of the existing inequities in providing benefits and the continued, systemic marginalization of an already marginalized population. But are there co-benefits that have not been fully realized? Consider the role of the building itself.

Green roofs

Local Law 92/94 in NYC became effective in November 2019. It essentially requires that all new buildings and alterations of existing buildings, provide a sustainable roofing zone covering 100 percent of the roof which must include either a solar photovoltaic system and/or a green roof system.

Green roofs, with far-reaching environmental, social, and economic benefits, can be instrumental in addressing systemic issues for Black, Indigenous and people of color (BIPOC), as well as low-income populations; too often one in the same.

When the greenery on a roof elevates to being productive, a chain of reactions can drive home the point that the cost of installing and maintaining a rooftop garden or farm begins to diminish relative to the co-benefits it can provide: entrepreneurship, job training, educational opportunities, community building, access to local food, support for shelter-in-place and greater resilience amidst extreme heat and disruptions to the food system.

This begins to address health issues as well as providing cleaner, cooler air. Since the Department of Housing and Urban Development still has not repositioned itself on considering air conditioning a luxury rather than a necessity (a long-standing position), this is an important benefit.

Shelter in place

Building on the opportunities afforded by a green roof creates opportunities for the residents to become self-sustaining and resilient in the face of disasters.

This was a major problem after Hurricane Sandy, especially in affordable and NYCHA housing. With too many elderly living on top floors in tall buildings without working elevators, they were not able to traverse the stairs, creating many difficulties for rescue crews trying to provide emergency supplies.

Underscoring the importance of equipping residents to shelter-in-place rather than be forced to leave during or after an emergency event, by integrating on the upper floors a kitchen, emergency-only medical station and at least one week’s storage of foodstuffs (supplemented by the rooftop farm), realigns the concept of resilience. It becomes its own circular form of self-reliance by being able to provide emergency supplies, from the top down as well as from the bottom up.

“We know that public housing is a sleeping giant. We are the most impacted by anything that comes to the city, whether it be COVID, registering to vote, filling out the census,” says Lynn Spivey, president of the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) Branch of the NAACP. “(I am) proud to advocate for people with NYCHA after growing up in public housing in the Bronx.”

Spivey serves as a HomeFree Champion, part of a Community of Practice and an advisory board for the national HomeFree initiative of the Healthy Building Network, supporting affordable housing leaders who are improving human health by using less toxic building materials.

Co-benefits are enhanced benefits that speak directly to quality of life. We all love to walk down tree-lined streets, especially in the summer, as they provide shade and cooling, filling our lungs with sweet, restorative air. This should not be a luxury enjoyed by those who happen to buy in the right real-estate market.

Quality of life is an environmental justice necessity. Co-benefits need to be provided equitably and fairly without distinction or prejudice. If we are all to survive the impacts of escalating climate change, we must rethink regenerative resiliency; otherwise, we will all pay the cost.

Valerie J. Amor is a member of the NAACP’s Centering Equity in the Sustainable Building Sector initiative, which is working to ensure a just transition to sustainable buildings for communities of color and low-income communities who disproportionately feel the burden of unhealthy, energy-inefficient, and disaster-vulnerable buildings.

You can also view this article as it was originally published on page 72 of the 2021-22 edition of the directory.