Asheville is known for being a small, mountain town nestled among the forests. Our urban tree canopy is prized by residents and visitors alike for its scenic beauty, wildlife habitat, climate change mitigation, cooling shade, and countless other values. A major benefit of trees in cities is that they enhance property values, and people prefer areas with tree-lined streets, shaded parks, and a beautiful diversity of trees, wildlife, and nature.

Unfortunately, these benefits are not equally distributed in urban settings, causing an inequality in urban forest canopy in the city.

Current research is now showing that this unequal distribution of tree canopy is not accidental, and can be traced back to historic inequality and housing discrimination. The historic effects of racially motivated discriminatory housing practices in the United States are still evident today.

Grading on a curve

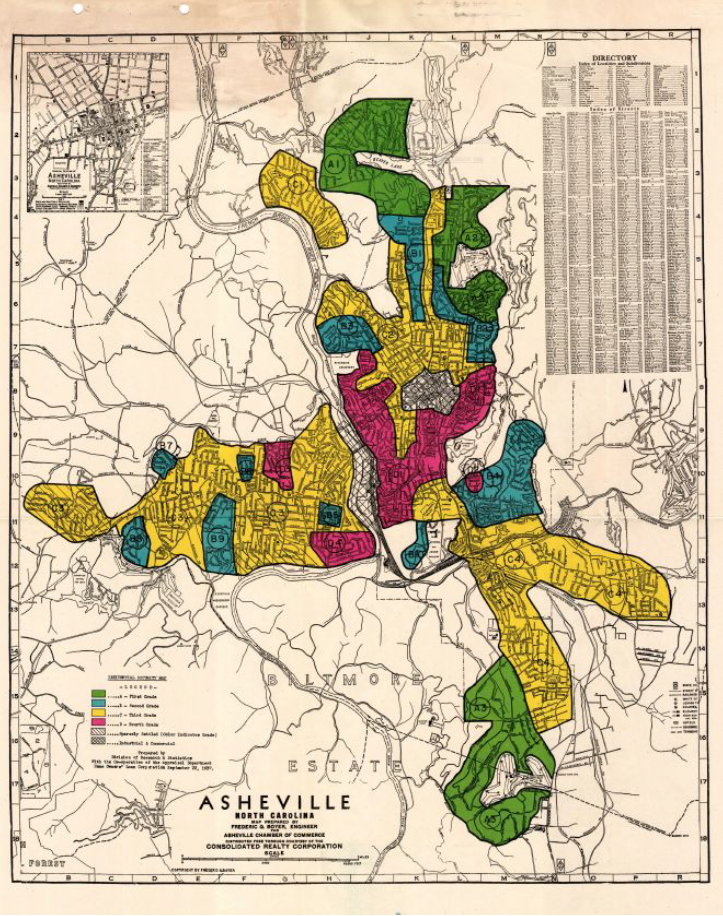

The federal government’s Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) graded neighborhoods in U.S. cities beginning in the 1930s and limited the ability of minority groups to own homes, creating a legacy of inequitable wealth distribution, home ownership, and other social and economic conditions that have persisted for generations.

Another product of historic redlining can be seen in the amount of tree canopy cover in U.S. cities, and studies from around the country continue to illustrate the correlation between urban tree canopy cover and HOLC-graded neighborhoods.

Scientists have used current tree canopy cover data combined with historic redlining maps to analyze how urban tree canopy cover varies within cities across the country. A recent study examined tree canopy versus HOLC-graded neighborhoods in 37 U.S. cities and found a significant difference in tree canopy cover today in those neighborhoods with an A grade from the 1930s as compared to those with a D grade.

In the historic HOLC grading structure, neighborhoods with an A grade were those that were characterized as the “Best”, with mostly white residents in newer housing stock. Neighborhoods with a D grade were those inhabited by mostly racial and ethnic minorities and were labeled as “Hazardous.”

The study found that D-graded neighborhoods have around 23 percent canopy cover today, compared to A-graded neighborhoods with nearly double the amount of tree canopy at around 43 percent on average.

This data combined with current research on the impacts of the urban heat island effect and other negative consequences of low tree canopy cover on humans and the environment clearly illustrate how these historic practices have created a legacy of inequity.

The local impact

In Asheville, work has begun on comparing historically redlined neighborhoods to assess existing tree canopy cover, but that research is incomplete.

When overlaying the historic HOLC maps of Asheville with existing canopy cover data, there are clear correlations and researchers are working on adding in socioeconomic data to get a better idea of this relationship.

A 2019 study on urban heat islands and tree canopy cover by NASA Develop did find areas of high heat vulnerability in Asheville when overlaying census blocks with high poverty or elderly populations with locations that lack tree canopy.

This combination of socioeconomic data and tree cover clearly illustrates where residents are most vulnerable to heat, particularly when combined with the lack of shade from trees. It is also easy to visually see the differences between tree-lined, canopy-covered neighborhoods in Asheville that are predominantly wealthier and historically in the HOLC A and B graded areas, compared to streets that lack tree canopy and are historically in the C or D graded neighborhoods.

The legacy of redlining is evident in Asheville, but the solutions are not as clear. Studies have shown that tree planting projects that simply put trees into neighborhoods where canopy is lacking have little chance of success. Tree planting and increasing tree canopy cover is a process that must involve local residents and foster community support and engagement well before any trees are planted. In Asheville we have strong neighborhood groups and community connections that can be rallied to include support for tree canopy preservation and planting programs.

A legacy of tree loss

The legacy of historic redlining practices continues to impact cities across the United States. Differences in current land use, socioeconomic factors of residents, and even tree canopy and urban heat island effects is apparent even more than 80 years later. The inequitable distribution of urban tree canopy cover leaves vulnerable populations more at risk from extreme heat, flooding, high energy costs, and other impacts from the lack of trees. Data from recent scientific studies can help to inform local and statewide decision making that can help to address these environmental and climate justice issues. While these studies make it clear that urban tree canopy cover is not evenly or equitably distributed in cities, they do not address some of the underlying reasons why some people choose not to have trees on their property, or why some cities do not actively work to improve tree canopy conditions.

Ongoing work performed by cities, environmental and tree nonprofits, and residents needs to be evaluated to determine which efforts are most successful in mitigating tree canopy inequity and addressing the reasons why these trends continue to persist.

Understanding how the legacy of redlining has resulted in inequitable tree canopy distribution in U.S. cities is one way that policy makers and citizens can begin to address this climate justice issue.

Amy Smith is a professor of science at Purdue University Global and a REALTOR® with Modern Mountain Real Estate in Asheville. She is LEED AP accredited and holds a Master of Science in Forest Ecology and Management, as well as a Master of Science in Environmental Policy. Amy serves as the chair of the Asheville Urban Forestry Commission and is a volunteer member of the Asheville Tree Protection Taskforce. Connect with Amy at asmithrealtor.com.

You can also view this article as it was originally published on page 52 of the 2022-23 edition of the directory.