The idea of off-grid living means different things to different people. Most presume, accurately, that it means not being connected to the power grid or a utility. Some imagine it’s about living a primitive lifestyle with no electricity at all or, at the other end of the spectrum, expensive and complex energy systems only the rich can afford. In reality, going off-grid does not have to mean a primitive lifestyle nor have to be incredibly expensive and, in fact, it can be affordable and very comfortable.

The first step, before addressing any technical aspects, is to examine and consider your motivations and your circumstances. Why do you want to go off-grid? Some want to go off-grid for important environmental reasons, such as the grid’s reliance on dirty fossil fuels and dangerous expensive nuclear power. Some want to go off-grid to save money. Some want to go off-grid for security and reliability reasons. Some find the cost of running a transmission line to a remote home site is more expensive than an off-grid system. There are many reasons to consider going off-grid.

As one who has been off-grid for over twenty years, my reasons were a combination of the environmental concerns, economics over time, desire for reliability and the cost of running a transmission line to the site. With my background in sustainable energy, it really was a no-brainer choice to make, even decades ago. But it’s not often that simple for everyone.

If you live in a home that’s already grid-connected, going fully off-grid for environmental reasons is tempting, however a grid-tied solar photovoltaic (PV) can meet your goals of clean energy with a balanced, net-zero energy system. The environmental challenges we face collectively with conventional grid-derived centralized energy are the result of power generated from non-renewable and dirty energy sources, not the distribution system itself.

The trajectory nationally and globally is towards a decentralized power grid system which means, in the simplest terms, transitioning from a central power generator that serves many tens of thousands to a distribution system that quite literally distributes power from many smaller sources onto the grid.

It’s true that there are challenges in implementing, modernizing and upgrading the grid system, however there are no actual technological barriers today. The more people who produce their own clean energy and share it with the grid, the better off we all are environmentally.

If you live in a home that’s grid-connected and are concerned about reliability issues, such as medical devices that need uninterrupted power, a basic battery-backup system charged by the grid can meet these needs in all but the most extreme weather events and outages. Whether a battery-backup system is charged by clean energy or the grid, there is emerging value for a decentralized grid in being able to both charge and withdraw energy (within parameters) to address peak demand and grid stabilization without needing to burn additional fossil fuels in a central power generator.

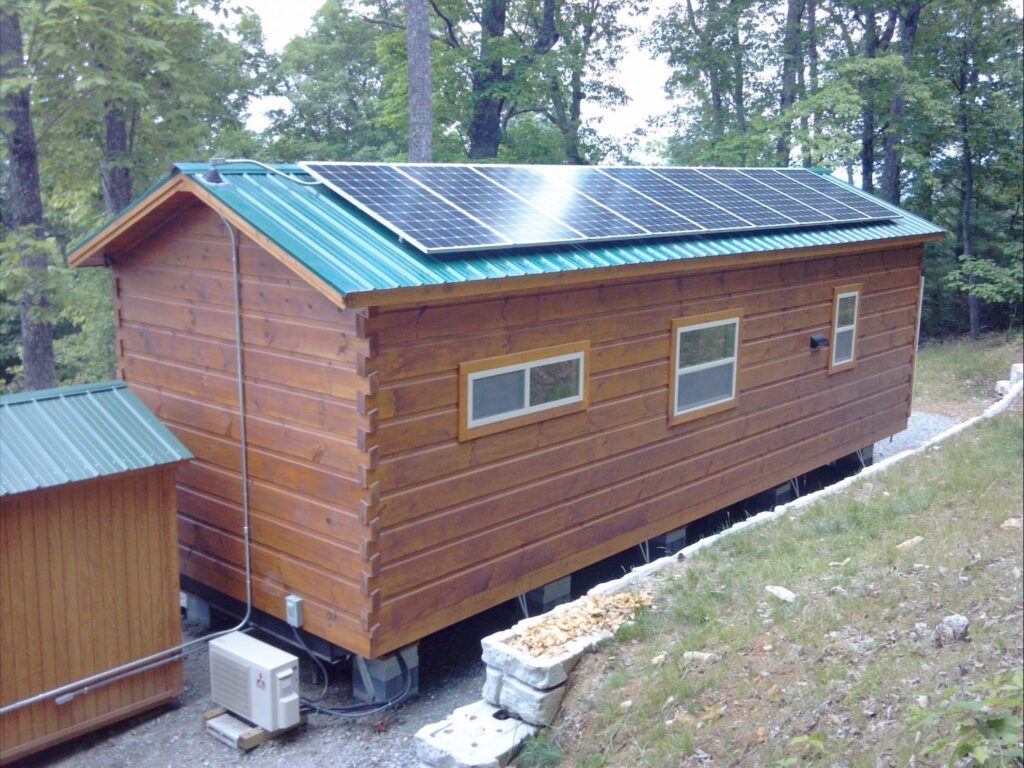

Roof-mounted solar photovoltaic panels offer clean energy while saving space in your yard. For best output in most cases, solar PV panels should be within 20 degrees of true south.

Interestingly, newer electric vehicles (EVs) can function as a battery-backup source in a power outage. In a best-of-both-worlds scenario, a home with battery backup, or an appropriate EV, and solar PV can support a decentralized grid while offering personal reliability in case the grid does fully go down for an extended period.

Going off-grid just to save money is more complicated, however it comes down to understanding that going off-grid is a solid long-term investment, not a short-term quick-profit scheme.

If you’re building a new home and taking on a mortgage that includes an off-grid infrastructure, the energy savings will cover additional costs in monthly payments for that system. To retrofit an existing home without financing, i.e. pay the cost upfront, there is still a payback in savings and tax advantages for now, typically in the range of seven to 10 years. In either case, financed or upfront, when the system has paid for itself in savings, you still have the capital investment in the home.

While an exceptionally better investment than buying a car, there are some parallels. Not everyone can afford a new car or high-quality used one out of pocket; nearly all cars are financed. Some folks can outright buy a Tesla; some folks take the transit bus.

If you have the money, or income to finance, it’s a great long-term investment. If you’re just getting by, it’s much better to invest in energy-efficiency measures to reduce your power bill.

It’s clear that investing in an energy system (off-grid or grid-connected) is far better than buying a car for the same price. At the end of 10 years, most cars have cost you thousands of dollars over the purchase price and are essentially worthless, or at best, worth a small fraction of the purchase price. On the other hand, at the end of ten years, you will have paid for an energy system which still has its value and will work for many more years.

One compelling economic reason to go off-grid is a remote location away from the existing power lines. The cost of having transmission lines run to a location varies, depending on terrain, distance and other factors, but can easily be $15,000 per mile or more. And then you get a monthly power bill! While my location is only about a quarter mile from the end of the power line, 20 years ago, the estimate was for between $5,000 and $6,000. A slam-dunk case for off-grid living!

If you’ve read this far and going off-grid makes sense for you to consider, great. Presuming you don’t have unlimited money to spend, here are a few essential tips on a practical level for the design and building an off-grid energy system.

No. 1, top priority: energy efficiency matters!

Do a comprehensive energy audit to determine where you need the power. In a new building, incorporate as much green design as possible, such as natural day lighting, plenty of insulation, solar orientation and other features to reduce demand and increase comfort. Retrofitting an existing building can be more challenging, however the same principles apply.

Use LED lighting—now available in different ranges, such as soft white, warm, white and daylight—to dramatically reduce lighting energy demands.

It’s virtually always less expensive to invest in high-efficiency appliances than to pay for extra solar panels, a larger wind turbine or more batteries to run cheaper, inefficient ones. This especially applies to refrigerators. Instead of a conventional electric water heater tank, consider solar thermal systems or gas on-demand water heaters. Instead of an electric stove, use a gas stove (generally propane for off-grid applications).

Design the battery bank for two to three days of power, rather than seven days. Rarely will it be cloudy, snowing or poor solar weather for more than a few days, and a small backup generator to charge the battery bank is far cheaper than designing for worst-case scenarios.

Perhaps most important, take an active role in understanding and interacting with your system. Unlike the “plug-and-pay” approach to being connected to the grid, your awareness of energy supply and consumption matters off-grid, not only for the costs but for a comfortable lifestyle.

It’s not a chore; it’s educational, informative and often interesting to have control over your own power. One of the joys I’ve found living off-grid (forgive me in advance) is when the winter blizzards hit, the grid goes down, and others face freezing pipes and cold homes, while I can follow it all on TV, perhaps choose a video to watch and relax comfortably until it passes.

Ned Ryan Doyle is a sustainable energy and environmental advocate with decades of experience and activism. Currently co-chair of the Energy Innovation Task Force’s Technology Work Group, he works from a personally designed and owner-built fully off-grid workshop powered by solar energy. Contact Ned at nedryandoyle@earthlink.net.

You can also view this article as it was originally published on page 20 of the 2017-18 edition of the directory.